A couple of months ago, I gave this book a quick skim and realized it talks about the idea of systems thinking. That instantly caught my interest and made me want to explore it in more depth. I was actually about to order a copy when, luckily, I came across the PDF edition provided by Florida Tech. A huge thanks to them for making this resource accessible.

Thinking in Systems by Donella H. Meadows was first published in 2008. The concept of systems thinking mentioned in the book is a perspective to solve complex problems that globally influence our societies, economies, organizations, and even the way we approach personal challenges in daily life. I liked the way she walked us through system parameters, behaviors, the common traps we fall into, and even the hidden opportunities we can tap into.

I enjoyed how the book made me look at problems with a systems mindset. This approach not only focuses on complex situations in companies, or even bigger problems that affect nations or the world as a whole, but it works just as well for personal challenges.

Honestly, I feel like this is the kind of book everyone should read if they’re stuck or just want a fresh way of thinking. It’s so practical that I’d even say it deserves a spot in postgraduate curricula.

As I was reading the book, I made chapter wise notes, and so I think this book review is more like my notes than a regular review. So, here are the notes:

Chapter 1: The Basics

As per Meadows, there are three fundamental components in almost all the systems – elements, interconnections, and purpose. For instance, the system of digestive system has:

- elements – stomach, intestines, teeth

- interconnections – how food moves through, how hormones signal different organs

- purpose – food digestion

Most importantly, changing elements usually has the least impact on a system. For example, replacing every player on a football team doesn’t make much of a difference if the coaching strategy and team culture stay the same, one will likely see similar results. However, changing the connections between players or the team’s purpose can transform everything.

The chapter then talks about stocks and flows. Stocks are things that accumulate over time, like water in a bathtub, money in the bank, or knowledge in our head, while flows are what fill or drain them, like a faucet, salary and expenses, or daily learning and forgetting.

This simple idea explains events or phenomena like why it takes months to get out of shape but years to get truly fit, or why traffic jams linger long after an accident is cleared, because the flow out is slower than expected. The author then brings in feedback loops, the engines of system behavior, which is, balancing loops keep things steady, like a thermostat, and reinforcing loops amplify change, like savings growing with interest or rumors spreading through a community.

Chapter 2: A Brief Visit to the Systems Zoo

Meadows then takes us on a tour of “systems in the wild”, putting forth how similar structures produce similar behaviors no matter the context. Thermostat, if placed in the wrong position, may give misleading readings. And same goes with business inventories, economic policy, and personal habits.

The author then explores growth systems, like economies expand through investment but face limits like resource depletion or market saturation. There are a few examples, like an economy powered by extracting oil will eventually face limits because of the depletion of the oil fields. The faster the extraction process is, the sooner it reaches those limits. This isn’t pessimism, it’s physics. After all, no finite resource can support infinite exponential growth.

Chapter 3: Why Systems Work So Well

After showing us how systems can create problems, Meadows explains what makes some systems remarkably robust and effective. According to her, there are three characteristics – resilience, self-organization, and hierarchy.

Resilience isn’t just bouncing back from problems, it’s the ability to keep functioning when things go wrong. Healthy systems build this through redundancy and multiple feedback mechanisms working at different time scales. One of the best examples is that our immune system has multiple ways to fight infections, similarly, a diverse ecosystem can survive the loss of several species. A well-run business can adapt when markets shift.

But this doesn’t work optimally all the time, for instance, just-in-time inventory systems look great on paper, as they save money and space, until a supply chain hiccup halts everything because there’s no buffer.

The author then moves to self-organization. These are systems that can create new structures and capabilities without any outside influence, like a baby learning language without any formal grammar lessons and cities, growing intricate patterns of neighborhoods and transportation without master blueprints. This happens when there is freedom to try new things and tolerance for some messiness. Organizations that try to control everything kill their capacity for self-organization.

Meadows then advocates hierarchy as she thinks it creates stability. Be it cells to organs to organisms to ecosystems. In case of organizations, when hierarchy works properly, higher levels provide coordination and support, not domination.

Problems arise when subsystems start optimizing for themselves instead of the whole. For instance, when a company’s marketing department focuses only on lead generation without considering whether the business can deliver on its promises.

Chapter 4: Why Systems Surprise Us

Meadows then talks about why even smart people get blindsided by system behavior. The reason is, we humans think linearly while systems often behave nonlinearly. We expect cause and effect to be proportional, but small changes can have massive impacts while large efforts sometimes produce nothing.

Another thing is “bounded rationality”. It means, drawing conclusions based on incomplete information and limited perspective, which every individual has. A farmer overgrazes land not because he’s evil, but because he sees his family’s immediate needs more clearly than long-term soil health.

Chapter 5: System Traps and Opportunities

This is an interesting chapter as it names certain patterns that we see them around so often. Meadows calls them system traps, and she runs through eight of them.

- Policy resistance, for example, is when different groups pull a system in opposite directions, so nothing really changes. Drug policy is a perfect example of that tug-of-war.

- Then there’s the tragedy of the commons, which shows up whenever people share a resource, like fisheries, roads, or the atmosphere, and each person takes a little too much, passing the costs to everyone else.

- Drift to low performance is another one, where standards slide slowly downward until mediocrity feels normal.

- Escalation explains arms races, price wars, and even those endless outrage cycles on social media, where each move triggers a bigger response.

- Success to the successful is the classic rich-get-richer effect, where small early advantages snowball into permanent ones.

- Shifting the burden is when quick fixes solve symptoms but weaken long-term strength, like painkillers dull the signal of an injury, and even well-intended aid can create dependency.

- Rule beating happens when people technically follow the rules but miss the spirit, like tax loopholes.

- And then there’s seeking the wrong goal, which might be the most dangerous of all, because a system will faithfully deliver what you measure, even if it’s not what you truly want. GDP rising doesn’t guarantee wellbeing, and higher school spending doesn’t automatically mean better learning.

What struck me is that Meadows isn’t saying “work harder” to escape these traps. She’s saying you have to change the structure of the system itself, otherwise the same patterns keep on repeating itself.

Chapter 6: Leverage Points

Now, Meadows here, ranks twelve different places where she thinks an individual can push a system to make change. Here are the pointers ranked from weakest to strongest:

- Numbers: tax rates, subsidies, budgets. Easy to change, but rarely transformative.

- Buffers: reserves like hospital beds or food storage that provide stability.

- Physical structures: roads, power grids, supply chains; costly and slow to alter.

- Delays: the lag between action and effect, like climate policies taking decades to show results.

- Balancing feedback loops: systems that keep things steady, such as thermostats or predator-prey cycles.

- Reinforcing loops: growth spirals like compound interest or viral rumors.

- Information flows: adding missing data shifts behavior, like real-time energy use on bills.

- Rules: laws, incentives, or regulations that define what’s possible in a system.

- Self-organization: a system’s ability to evolve, adapt, and reinvent itself.

- Goals: the purpose driving the system, like a company shifting from profit-only to broader social impact.

- Paradigms: the underlying mindset, such as seeing health as prevention versus treatment.

- Transcending paradigms: the rare ability to step outside assumptions entirely and remain flexible.

Her point is that most people pour energy into adjusting numbers, but the real leverage comes higher up, in rules, goals, and especially in the mindsets shaping them.

Chapter 7: Living in a World of Systems

The final chapter acknowledges that understanding systems doesn’t mean controlling them, rather, Meadows urges us to “dance with systems”, which means staying alert to what’s actually happening instead of forcing rigid plans. She also reminds us to question our own assumptions.

Another equally important area is, information flows. When people have access to clear & timely feedback, systems tend to work far better.

She also warns against obsessing over what’s easy to measure while ignoring what truly matters, like joy in learning, compassion in healthcare, or wellbeing at work. Another principle is designing responsibility into systems so decision-makers feel the consequences of their choices, pilots fly the planes they steer, so why shouldn’t CEOs live with the impacts of their companies, she questions.

Takeaway

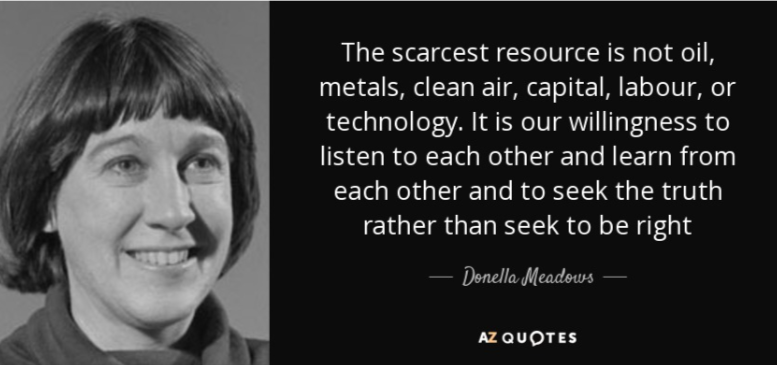

The last part of the book is more reflective. Meadows isn’t saying we can control complex systems perfectly, we can’t. But we can get better at working with them. Here are a few takeaways:

- Pay attention to patterns, not just one-off events.

- Be honest about your assumptions and update them when needed.

- Share information openly and clearly.

- Don’t fall into the trap of only measuring what’s easy. Some of the most important things, like justice or trust, can’t be counted.

- Listen to what the system is trying to tell you. Sometimes it knows better than you do.

- Always leave room for learning. Stay curious. Don’t expect to have all the answers.

- Finally, keep the goal of doing good front and center. Even when it’s not easy or popular.

This book doesn’t offer quick fixes. It’s more like learning how to read a map of something you’re already in the middle of. Once you start seeing the loops, stocks, delays, and purposes around you, it’s hard to unsee them. And that’s exactly the point.

Finally, this book forced me to think or question maybe – once we start seeing the world as a web of systems, can we ever go back to looking at problems in isolation?